For decades, migraines were dismissed as “just bad headaches.” That view is finally changing. Scientists now understand migraine as a complex neurological disorder that affects the entire body, not just the head. As research advances, long-held ideas about triggers, symptoms, and which parts of the brain matter most are being challenged.

For people who experience migraines regularly, the pain can feel deeply personal and unpredictable. It may start as pressure on one side of the head, spread behind the eye, burn, throb, or pulse, and linger long after medication wears off. And for more than 1.2 billion people worldwide, this is not an occasional problem. Migraine is the second leading cause of disability globally.

Yet despite how common it is, migraine remains one of the least understood neurological conditions.

A Disorder We Still Don’t Fully Understand

Migraine is not caused by a single factor. According to researchers, it involves a combination of brain activity changes, nerve signalling, blood vessels, genetics, and chemicals released in the nervous system.

“It’s probably among the most poorly understood neurological disorders,” says Gregory Dussor, chair of behavioural and brain sciences at University of Texas at Dallas.

What makes migraine especially difficult to study is that it is not limited to pain alone. It often comes with nausea, sensitivity to light and sound, visual disturbances, fatigue, and cognitive fog. These symptoms can begin hours or even days before the headache itself.

What’s Actually Happening in the Brain?

Recent studies suggest that migraine begins with abnormal electrical activity in the brain. Researchers have observed waves of altered brain signalling, sometimes called cortical spreading depression, moving slowly across the brain’s surface. This activity is believed to trigger inflammation and activate pain pathways.

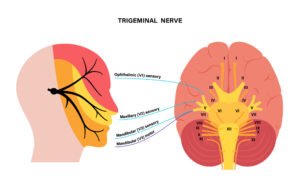

One key system involved is the trigeminovascular system, which connects facial nerves to blood vessels in the brain. When this system becomes overly sensitive, it releases inflammatory molecules that amplify pain signals. Scientists have also identified specific chemicals, such as CGRP, that play a major role in sustaining migraine attacks. This discovery has already led to new, targeted treatments.

Importantly, many things once thought of as “triggers” such as light sensitivity, food cravings, or neck stiffness may actually be early symptoms of an attack that has already started.

Why Migraine Research Lagged Behind

Migraine research has long been held back by stigma. In the 18th and 19th centuries, migraines were often described as a condition affecting only emotional or “hysterical” women. While about three-quarters of migraine patients are female, this outdated framing damaged the credibility of the condition for generations.

“People thought of it as a disease of hysteria,” says Teshamae Monteith, chief of the headache division at University of Miami Health System.

Even today, few universities have dedicated migraine research centres, and funding remains low compared to other neurological disorders with similar levels of disability.

A Shift Toward Better Treatment

The good news is that momentum is building. Advances in genetics, brain imaging, and molecular biology are helping researchers see migraines unfold in real time. This has reshaped how doctors think about treatment, moving away from masking pain toward preventing attacks altogether.

Rather than being a simple headache, migraine is now recognised as a chronic neurological condition that affects the brain, nerves, blood vessels, and body systems together. Understanding that complexity is key to improving treatment and quality of life for millions.

As science catches up, migraine is finally being taken seriously, not as a nuisance, but as the disabling condition it truly is.